The last and least familiar chapter in his trilogy of cloistered biopics, Pablo Larraín’s “Maria” is — like “Spencer” before it — a beautifully designed but sparsely furnished mind palace of a movie about a famous 20th century woman struggling to see herself through the inescapable glare of history’s spotlight. Where the opera star Maria Callas differs from Princess Diana or First Lady Jackie Kennedy in Larraín’s conception is that she desperately wants to be on (or return to) the public stage; her most authentic self is only complete with a loving audience.

The trouble is that “La Callas” has a tendency to be conflated with her characters. Tosca. Turandot. The exploited daughter. The unreliable diva. She is all of these things, but also none of them and so much more. Four years since her failing health forced her into early retirement at 49, and one week before she’ll die of a heart attack on the floor of her musty Paris flat (where her body is found in the film’s opening scene), Callas is determined to perform the role she born to play — even if it kills her.

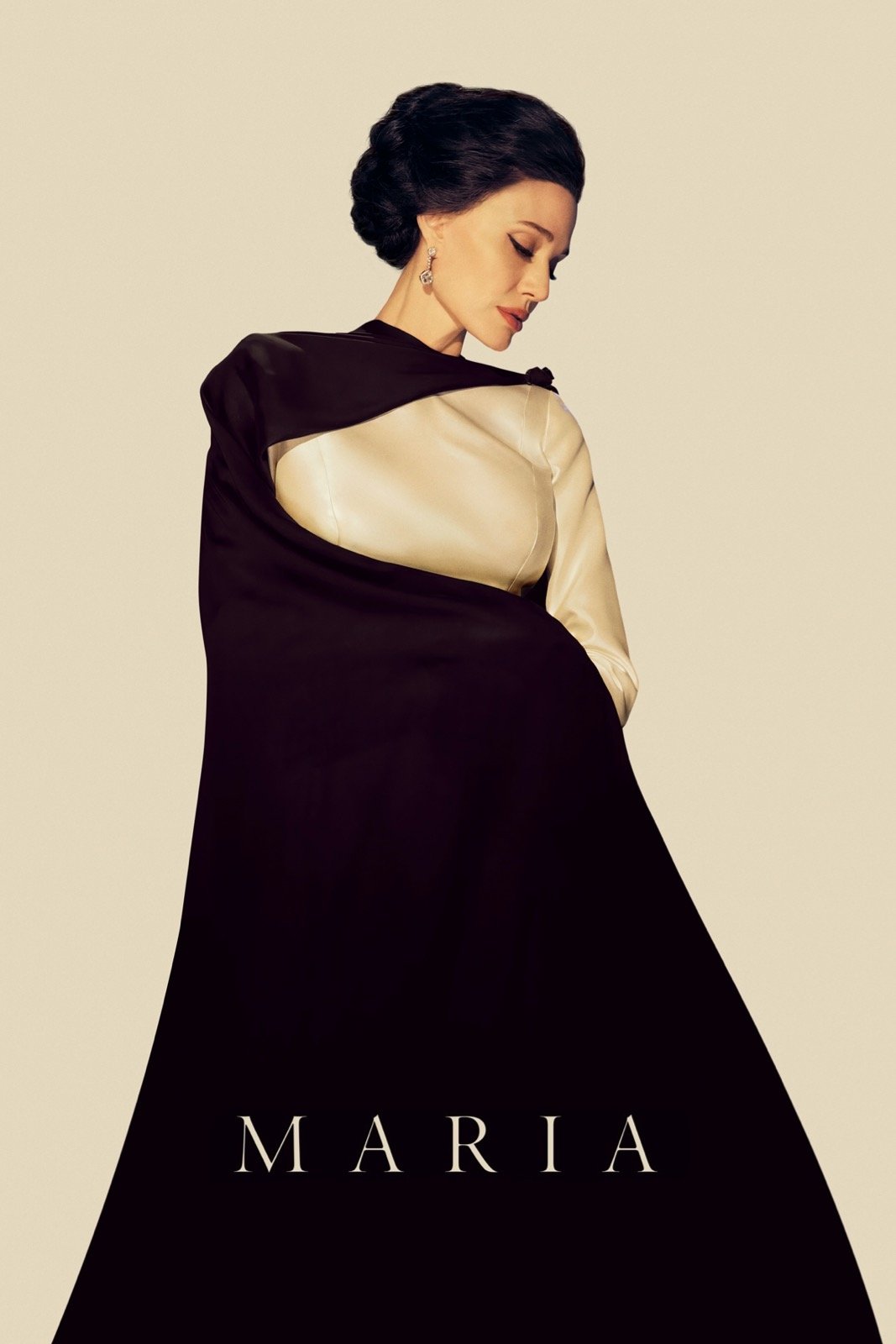

And yet, despite the richness of Larraín’s directorial vibrato, and the haughty (but tenderly knowing) spectacle that Angelina Jolie makes of his latest muse, the specifics of Callas’ immortal essence remain frustratingly vague. “Maria” — again, much like “Spencer” before it — is at once both nebulous and overwritten. In stark contrast to “Jackie,” the only installment of Larraín’s trilogy that wasn’t scripted by “Peaky Blinders” creator Steven Knight, this claustrophobic psychodrama is so focused on freeing its subject from her own legend that it struggles to convey who she is or was beyond it.

While “Maria” cleverly illustrates how Callas’ life was the stuff of opera itself (and therefore immune to the drudgeries of reason), Larraín’s freeform portrait of the diva’s final days seldom feels like more than a libretto: passionately sung, but lacking the detail and fullness needed to bring it to life.

All three of the films in Larraín’s trilogy are sustained by their emotional generosity (by offering their subjects the empathy they were denied when they needed it most), but Knight tends to root that generosity in the same dull pitiableness that “Jackie” was so powerful for avoiding completely. “Maria” introduces its namesake as a caged and molting songbird who shuffles around her mahogany apartment like a Quaalude-addicted Norma Desmond — albeit one who’s a bit more loving toward the help.

Suffering from a combination of ailments that vocal researchers have since ascribed to dermatomyositis, the Callas we meet in the fall of 1977 is too fragile to mount a comeback; so much of herself has been taken away over the years, to the point that her curls have become the thickest part of her body. When she needs an audience, she belts out an aria for her loyal housekeeper (the great Alba Rohrwacher). When she needs an adversary, Maria gently tortures her wincing manservant (“The Traitor” actor Pierfrancesco Favino). And when she needs adulation, she sits outside at the local café and waits to be recognized, even if that makes her an easy target for the bitter fans who bought tickets to some of the concerts she canceled toward the end of her career.

To that end, Larraín’s trilogy remains unusually nuanced in its double-edged depiction of the relationship between icons and their public, and Callas — even while losing her grip on reality — is all too clear-eyed about what people want from her. As she says of her dogs: Their dedication is 99 percent motivated by food, and one percent by love. That dynamic puts her at a certain distance from the rest of the world: the same distance that separates a theater audience from the stage. As a result, even Callas’ private life is set against a heightened reality, and she can’t even walk past the Eiffel Tower without a horde of strange men barking at her in baritone, or sneak into the opera house where she’s secretly hoping to sing again without being watched by the ensemble cast of “The Mikado.” While not especially insightful, such flourishes nevertheless provide welcome opportunities for Ed Lachman to show off the soft grandeur of his gorgeous 35mm cinematography.

The line between fact and fantasy isn’t hard for us to define, nor is it meant to be in a film so determined to let Callas reconcile the two on her own terms. “What is real and what is not real is my business,” she purrs at one point. “There is no life apart from the stage,” she declares at another, “and the stage is in my mind.” She insists that she’s happy with “the theater behind my eyes,” and the movie refuses to end until we believe her.

SpoilerIndeed, “Maria” commits to that conceit at the expense of everything else, as Knight and Larraín contrive to create a vision of the autobiography that Callas never lived to write, a nonlinear approach that explains the overly sculpted dialogue, paves the way for several lustrous black-and-white flashbacks and — less compellingly — allows for a recurring bit in which the diva is the subject of an imagined documentary that’s being directed by a reporter named “Mandrax” (Kodi Smit-McPhee, looking suitably unreal), which was the European brand name for Quaaludes. From the opening title card, which is written on a film slate, to the climactic sequence, which effectively returns the singer to the stage without betraying the fact that she never performed again in real life, “Maria” is graciously determined to restore Callas’ voice in every sense.

The reasons why Callas feels that her voice doesn’t belong to her are at once both obvious and inscrutable. When Callas was a teenager in Nazi-occupied Greece, her mother forced her to sing for their supper, and it’s implied that the girl’s soprano compelled the SS not to exploit the rest of her body along with it. When she began a well-documented and long-lasting affair with shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis (Haluk Bilginer, gravel in his throat and Mastroianni in his hair), he “forbade” her to sing, preferring that she belong to him rather than the rest of the world.

Of course, Onassis himself never belonged to her, and his eventual decision to marry the widowed Jackie Kennedy helps bring Larraín’s trilogy full circle (I’m ashamed to admit that some part of my Marvel-corrupted lizard brain was holding out hope for a Natalie Portman cameo). The world took liberties with Callas, and — in the final days of her life — she’s dying to take them back. That much is clear. But Callas’ need to reclaim herself is far better defined than what she needs to reclaim herself from, or even what that reclamation might hope to entail. Callas’ emotions are all volume and no depth. Her relationship with Onassis has the nuance of a tabloid gossip column (though “Maria” makes a meal of the admission that Callas enjoyed feeling “like a girl”), and her family history is painted in such unhelpfully broad strokes that Valeria Golino is helpless to save it with her one-scene performance as Callas’ sister.

If not for Jolie, it’s possible that “Maria” would feel like another form of the unfounded scrutiny that made Callas’ life so miserable; more sensitive, perhaps, but still cobbled together from echoes that are made to sound like a single voice. Jolie gives this immaculately adorned movie a much-needed sense of interiority. Callas may be straining to find if she “still has a voice,” but Jolie’s sharp transatlantic drawl fills the space around her, even in its frailty. Jolie may not be doing all of the singing (as it was with Rami Malek and Freddie Mercury in “Bohemian Rhapsody,” a recognizable percentage of the actor’s voice is interpolated into Callas’ recordings), but you can practically see the music coming out of her mouth with every note.

Larraín is well aware that he’s casting one tabloid sensation to play another, to the point that it almost seems as if he’s counting on that metatextual resonance to make up for the script’s lack of specificity; or even that the script’s lack of specificity is a deliberate gamble to leave room for the metatextual resonance of the film’s casting. Whatever the case, Jolie’s broadly theatrical but delicately unraveling performance feels immersive and self-revealing in equal measure, as if Maria Callas is a conduit for her to reclaim her own identity as an artist and a human being.

Like Larraín’s other heroines before her, Callas belongs to “the magical group of people who can go anywhere they want in this world, but can never get away,” and there’s no doubt that Jolie belongs to that magical group as well. In the harmony that she creates with Callas, and by extension in the harmony that she allows Larraín to create with Princess Diana and Jackie Kennedy beyond her, these women give each other the lasting escape they had to find from within, but could never keep on their own.

Estreno: 7 de Febrero, 2025

Estreno: 7 de Febrero, 2025